Brady Error and Suggestive Pretrial Identifications

Whether or not an in-court identification of a defendant by a witness is tainted by a suggestive pre-trial photo lineup identification depends upon the circumstances. The suppression by the prosecution of evidence favorable to an accused, whether intentional or not, violates due process, at least where the evidence is material either to guilt or to punishment, and whether or not the defense has made a request for such evidence.

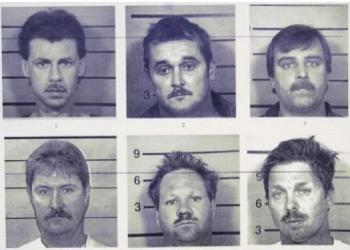

Defendant David Bruce was a guard at the United States Penitentiary at Atwater, California. Another Atwater prison guard—who soon became key to the issues in this case—was Paul Hayes. On December 12, 2015, a local resident, Thomas Jones (and his wife), attempted to pay a visit with an Atwater inmate by the name of Devonne Randolph. The Joneses had developed a scheme with Randolph whereby they would receive packages containing drugs and other contraband for him and bring them as far as the Atwater Prison’s parking lot where they would be delivered to an intermediary known to Jones only as “Officer Johnson.” Officer Johnson would then smuggle the packages into the prison itself. Although this scheme working successfully in October and November, 2015, a third attempt on December 12th did not go quite as expected. Stopped and subjected to a random prison parking lot search, (the legality of which was not in issue; see Cates v. Stroud (9th Cir. 2020) 976 F.3rd 972, 983-984.), the officers found four vacuum-packed bags of marijuana, a package of heroin, and three marijuana cigarettes in Jones’ car. Present and participating in this search was prison guard Paul Hayes. Faced with drug smuggling charges, and hoping to avoid becoming an inmate himself, Jones was very cooperative with the ensuing investigation. First, Jones helped to identify the man who referred to himself as “Officer Johnson.” In addition to providing a detailed physical description, Jones indicated that Officer Johnson commonly wore a Pittsburg Steelers hat. Knowing that defendant wore a Steelers cap, the officers showed Jones a Facebook photo depicting defendant sporting such a cap. Jones identified defendant without hesitation as the man he knew as Officer Johnson. With this information, prison agents set up another parking lot meeting scheduled for several days later. With Jones’ cooperation, agents went to the prison parking lot and sent out a text message as if from Jones, announcing the arrival of another delivery. Within minutes, defendant responded to the parking lot driving his personal vehicle, circling the parking lot several times as if checking out the scene, and slowing each time as he passed Jones’ car. Rather than wait until defendant made contact with Jones, the agents stopped him as he continued to drive around the parking lot. Despite being caught red-handed, defendant denied that he was there to receive a drug shipment. Defendant was indicted by a federal grand jury some fifteen months later—in March 2017—and charged with conspiracy, attempted possession with intent to distribute heroin or marijuana, and accepting a bribe as a public officer. Although not clearly explained in the Ninth Circuit’s written decision, a possible defense available to defendant early on was what is sometimes referred to as a “Soddi” defense; i.e.: “Some other dude did it.” In arguing such a defense, defendant claimed that his only transgression was participating in some illegal sports wagering. With an issue as to the possible unconstitutional suggestiveness of Jones’ identification of defendant as the man he knew as “Officer Johnson,” having identified defendant from a Facebook photograph in which only two people were depicted and with only defendant wearing a Steelers cap, what was considered at that time to be a dearth of any other evidence connecting him with Officer Johnson’s illegal drug-smuggling activities was no doubt a concern to the prosecutors. The government therefore filed a written pre-trial ex-parte motion for the court’s in camera review (excluding defense counsel), asking for a ruling to the effect that the government need not disclose to defendant certain information about two other Atwater prison guards; one of them being Paul Hayes. In the motion, it was disclosed to the court that Hayes was present during the search of defendant’s vehicle, but explained that the government had no intention of calling him as a trial witness. The government’s motion further disclosed to the court that Hayes’ personnel file contained potentially incriminating information, including seventy-plus inmate complaints (some of which, it later turned out, involved Hayes coercing inmates into testifying against defendant). Significantly, it was disclosed to the court that, subsequent to the events described above, Hayes came under investigation for smuggling drugs at another federal prison in Victorville, California. What the government’s motion did not include was anything to forewarn the court that defendant had an option of arguing a “Soddi defense,” and that Hayes—given his history of alleged abuses of inmates and drug-smuggling activities—was a good candidate to be that “other dude.” The trial court granted the government’s motion. As it turned out, the case against defendant proved to be relatively strong. At trial, Thomas Jones positively identified defendant as the guard to whom he delivered the contraband. Also, an inmate by the name of Robert Rush testified to helping with the distribution of the smuggled drugs and the collection of the resulting proceeds from the inmates, which Rush split with defendant. Money transfer and cellphone evidence linking the various parties to defendant was also introduced. The jury convicted defendant on all counts. Shortly after defendant’s conviction, however, Paul Hayes was indicted in federal court on charges of drug smuggling at the Victorville prison, to where he had since been transferred. Although the investigation of Hayes’ alleged drug smuggling did not begin until some sixteen months after defendant was indicted, defendant’s trial wasn’t to begin for another seven months. It was during this seven-month period that the government filed its pretrial ex parte motion in defendant’s case, as discussed above, to prevent this new information about Hayes from being released to the defense. With all this new evidence coming to light, defendant filed a motion for a new trial, alleging “Brady error.” (Brady v. Maryland (1963) 373 U.S. 83.) Bruce’s motion centered on the argument that he should have been informed that Hayes was the target in the very similar Victorville drug smuggling investigation. He also should have been told that Hayes had been actively engaged in coercing Atwater prison inmates into testifying against defendant. Defendant argued that Brady v. Maryland imposed a pretrial duty upon the prosecution to provide such evidence to the defense. Despite being somewhat irritated that the government had misled him in its pretrial ex parte motion, the trial court judge denied defendant’s motion for a new trial, ruling that even with the potentially exonerating evidence that, under Brady, should have been revealed to the defense, the existing “overwhelming evidence that supported the jury’s verdict (against defendant) completely and totally” justified the denial of defendant’s new trial motion. The Ninth Circuit was thereafter called upon to review these findings.